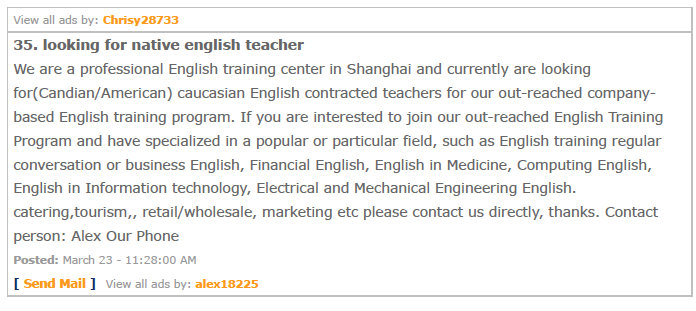

On-line ad seen in 2004 in Shanghai.

UNFINISHED BUSINESS

An article I saw in a Shanghai arts/guide/social scene publication in the Fall of 2007 prompted me to pitch this piece which ran February 13, 2008 on Marketplace. The article, which I knew to be a deliberate misrepresentation, inferred that there was widespread acceptance, in emerging China, of persons of African ancestry. From personal experience I knew this to be untrue. By that time I had lived in Shanghai for five years.

I am of European ancestry. The article riled me. I met the author last Summer, 2008. She is a lovely, lovely foreign (non-Chinese) woman who substantiated my feelings. What she had tried to do, as is done so often in China and elsewhere, is write an accurate story.

Working In China While Black

By Bill Marcus

Barbara Landsberg is a victim of racially discriminatory hiring in Shanghai and she is grateful for it. Twelve years ago in Shanghai her prospective German boss forced her to choose between her romantic relationship with an African man and a well-paying position as a human resources manager for a shipbuilding company with 300 employees, many of whom were form the Chinese countryside.

“He just had a feeling that it would affect their workplace. The Chinese employees would not give me enough respect,” said Landsberg, whose name has been changed at her request. “That made the decision very easy that I didn’t want to work for him.”

Another woman from West Africa who traded candidness for anonymity was not as grateful. When, in 2004 she did not get a position as a secretary at a Shanghai joint-venture law firm because of the color of her skin, she felt as if her prospective Shanghai employer had pulled China’s proverbial welcome mat out from under her feet, she said. Never mind her fluency in Chinese and an undergraduate degree from one of Shanghai’s top universities, which had invited her to study with a scholarship.

“One lady said, ‘We really don’t want black people – no good reason, that’s what the boss said.'” The gate to Shanghai’s entry-level job market was closed to her.

Race discrimination has a targeted economic impact. It denies opportunity to otherwise talented professionals, deprives companies of the benefits of a diverse work force, and profoundly hurts China’s standing in the global community at a time when the country negotiates global roles as business partner to Africa and as host to the upcoming Beijing Summer Olympics and the World Expo 2010 in Shanghai.

Yet its most insidious impact is its acceptance by a select subsection of foreign managers. These foreign managers feel they have the right to employ racial bias because their actions will not tamper with relations with Chinese clients and customers, according to numerous white-collar African workers in Shanghai affected by such actions. These workers, in turn, have no clear course for a redress of grievances.

“You’re white: you’re brilliant, you’re intelligent, you’re rich; you’re black: you’re foolish, you’re poor, you’re not intelligent,” concluded the West African woman, one of a growing pool of disenchanted Shanghai workers, about he lay of the land for blacks in China.

“I think this is a long journey,” said He Wenping, Director of the Africa Office of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, in Beijing. For contrast, she noted that racial discrimination in corporate America remains a persistent problem. “Even if it’s a separate isolated example, we should face it with the highest degree of responsibility and find the right way to solve it,” she said. All of the stories she was told were new to her. “The correct point of view is to face it and to find out what is the reason.”

Blacks interviewed for this article say it’s that general willingness to change, grown and learn that keeps them here so both they and China can continue to make progress, even if the circumstances are far from perfect.

Mutual understanding among different races and reconciliation are up against a tough fight when Chinese corporate and government leaders do not even recognize the discriminatory ways. A London Sunday Times article last November on China’s growing involvement with Africa placed this ignorance in the sharp relief of black type on white paper. It reported that Heng Zequan, vice-chairman of the Sino-African People’s Friendship Association, told China Business Daily, “African people, generally speaking, have little idea of finance. They like to spend all the money they have and, therefore, there’s a very good market for Chinese products there.”

The Times article also re-quoted an unnamed pharmaceuticals manager commenting in the Shanghai Communist Party daily Jiefang Ribao as saying, “African people’s rhythm of life is very slow and they also treasure their lives very much and enjoy entertainment, so they do not want to work overtime. So we don’t ask them to work at night or do overtime.”

“Diversity in organizations is not widely practiced in China,” said Shook Liu, Shanghai-based managing consultant of Hudson, the global recruitment firm headquartered in New York City. The cost of such neglect is starting to add up.

William Dodson, managing director of consultancy Silk Road Advisors, characterizes the Chinese mindset in this way: “White people are the one who – right now – have all of the economic and military might in the world. They may not have much culture, the Chinese believe, but they’ve got what we want – now.”

He says he believes his Chinese fluency, ‘coffee=-colored’ skin tone and generally positive disposition spares him racial discrimination. “At least outside of the United States, nine-tenths of discrimination is how you present yourself,” said Dodson, who is American.

“For most of the Chinese people, a black image is related to refugees, poverty, Africa,” said Sarah Feng, who founded the Shanghai-based talent agency, TI Models in 2005. Her observation, she said, should be interpreted as a reflection of those around her, and not a statement of fact.

Actors from blended or mixed backgrounds, especially those of French or American and African ancestry have a greater chance to work in commercials in Shanghai than a “pure African-looking black,” she added. “We don’t have many opportunities for black talent.” For every 20 jobs for a white foreigner, there will be one job for a black foreigner, according to Feng.

The handful of black models who do find television commercial work in Shanghai usually end up typecast as a runner or a basketball player, Feng said. But, ironically, like all foreign extras, they earn 10 times as much as a Chinese model doing a similar job. Wages are driven by supply; Chinese extras are much easier to find than foreign actors, regardless of skin color. Middle Eastern, Indian and Russian actors face similar discrimination, she said.

“I don’t think Chinese people are that racist. Chinese people are more money-oriented,” she said.

Still, advertisers that sell products and services to the Chinese market nurture this overall perception: a black actor will not sell as well as someone who is not black. And so do the businesses making money teaching English as a second language. All things being equal, black candidates will get a job before an Asian American “because the black person looks more like a foreigner,” said one teacher who holds a Ph.D. and asked that her name not be used.

“They only call you when they are desperate, when the white teacher is not available,” she said. “As a black teacher you have to work twice as hard to prove yourself; even if you are sick, you go to work.”

When blacks do enter the classroom, they often face a rude, cultural bluntness from students, co-workers and parents. The teacher mentioned above shared the story of how a disruptive Chinese 10-year-old last June rebuffed her by screaming out “You’re blaaaack!” “I had to explain to him that the color of my skin has no bearing on your competence or what I came here to share with him,” she said.

The result of favoring against American-born and –educated blacks and Asians by some English programs would be laughable for many if it weren’t so blatant. White Eastern European teachers who speak in Polish or Russian Pidgin English are routinely given access to classrooms where they revel in a lack of native tongue knowledge. Public and private school language programs for children and adults eventually pay for their prejudice by turning out a crop of unskilled Chinese students; they reduce their product value and long-term credibility as a business. Firms that hire these graduates also end up with inadequate workers.

Unlike many Western countries, where laws criminalize discrimination in advertising, several schools in Shanghai explicitly exclude blacks and Asians from their recruiting campaigns and routinely discriminate against non-whites in hiring and promotion.

When a Shanghai-based ‘professional English training centre’ ran an online advertisement seeking a “(Canadian/American) Caucasian” teacher, they effectively ruled out hiring 43 million Americans of African ancestry, countless African Canadians, 10 million or so North American-born Asians not to mention millions of Latinos, Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, Inuit and others.

In 2004 Boston native Virginia Hunt was hired over the phone to direct an English summer camp in Shenzhen. She as fired soon after she showed up.

“When I actually landed and met the person who had hired me, I could tell from his face that he wasn’t expecting what he saw,” said Hunt who had sacrificed another opportunity in Shanghai to pursue the camp job. When she returned to Shanghai she contacted the American embassy and a law firm but abandoned her retaliatory efforts when she was distracted by a family emergency and had to return to the United States. “They were trying to hire more so for marketing purposes. They wanted to have, like, you know, certain types of faces of people as displayed on their camp, maybe, website to bring in more students.”

But Hunt also reported progress. Parents of one of the classes she taught in Shanghai were “very upset that I was teaching their children,” she said. “One of those parents is the one who is a strong supporter of me now.”

“They give you a fair chance to change their minds, and this is not something you find in other societies,” said Anna Rundshagen, an inter-cultural communications specialist who has lived here and worked with Chinese organizations for the past 14 years. “They notice you a lot but after you’ve worked together for two weeks you are one of us.” Rundshagen called the Chinese way of perceiving differences in others as “cultural stereotyping”.

Inter-personal workplace struggles, including those between Japanese, Korean and Chinese that are driven by history and nationalism are more difficult to navigate, as are rifts in the Shanghai workplace that exist between Shanghainese and workers from outside Shanghai. Experts say managerial persistence is necessary to mitigate these regionalist stresses.

While racial prejudice is the root of workplace discrimination, it is also the basis of a multi-million dollar business in China: skin whiteners. It’s not unusual for the average woman to plunk down US $70 for skin whitener, the fastest growing sector of the prestige beauty industry in the country, according to NPD Group, a market research firm headquartered in Port Washington, New York.

“The use of whitening products starts at a very young age in China and continues through adulthood. This is a product that is more popular in Asia and we see this trend continuing to grow and gain strength in the coming years,” said Edward Wang, manager of China beauty at The NPD Group in a statement in January.

In the absence of corporate or government initiatives, members of Shanghai’s black business community take action where they can. The Caribbean Association of China, created last spring by Nicoleen Johnson, owner and manger of China Trade Consulting, regularly donates time to tutor English to the children of migrant workers at the Changlin Primary School in Pudong. In the process she and other teachers introduce the children to Caribbean culture and the notion that not all black people come form Africa. “They love it,” said Johnson, who holds a Ph.D. from Fudan University. “The teachers and principals ask us when we are going to come back.”

Corporate trainer Imani Kimu Payne of New York State says he makes a point of introducing taboo and cross-cultural relationship to his clients. He also gets an overwhelmingly positive response, he says.

“I feel it’s my duty because I don’t know how many times seemingly educated Chinese professionals have said something like, ‘Wow, you look exactly like (Houston Rockets basketball star) Tracy McGrady!’ or ‘You must be able to dance very well.'”

Even the West African woman who didn’t get the legal job is hopeful for change. “If it’s going to happen, Shanghai will be the starting point,” she said.

—30

Related Honkies For Hire, Global Times, April 1, 2010

Related – The World: Western expats in demand in China, July 9, 2009

Related – Marketplace: Racism a battle in Chinese workplace, February 13, 2008