When we leave our homes for someplace else — another country — we are often looking not just for what awaits us there, but how the new place may help us come to terms. My teaching assistant in the first class I took when I returned to graduate school in the mid-90s, a Chinese woman still grieving her late dad, told me at the time she hoped religion in America would help her. In the end, it didn’t. Not because it wasn’t there to be found, but because by her age and with her history growing up during the hyper-political Cultural Revolution she had no tradition with which to connect to an American God. She just couldn’t automatically “plug in” no matter how much she wanted to. A theological solution to her grief would not be willed.

Searching for something to believe in is what motivates Christians in China. The momentum of Christianity’s draw has eclipsed Communism. Some in the government are eager for the masses to embrace religion as a possible solution to the exigencies of capitalism. The theology, they like. It’s the sociology – the institutions, customs, and empowered groups: that, Communists in China fear. It’s competition. A challenge to the Party’s primacy.

AA & NA in China – at the table AND on the menu

A similar cautious embrace was made by officials in Beijing charged with fighting China’s drug problem who reached out to a friend who had started an Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous group in Shanghai. But there, too, the effects of the Cultural Revolution linger.

China’s Narcotics Anonymous groups struggle, he told me, because it’s difficult to build trust. As a result, Chinese addicts, despite being at the table are still on the menu.

Moral Voids

When it comes to filling one’s moral void in China, culture is the default. Other people are a necessity. Seated in a near-empty restaurant in China will be two parties next to one another. Ask for directions on the street and a conference will break out. Everything is better with a group.

Even justice. If you hit another car (or pushcart) both you and the person you hit get out and argue on the spot. A Greek-like chorus of unrelated individuals and onlookers gather to arbitrate, or, to take in the event’s entertainment value. A resolution reached, money is exchanged. Both drivers then get back in their cars and drive away. No points. No increased premiums. No court-ordered driving course.

Taxi fares

Once, in anger, I inadvertently took the door handle off a taxi that refused to open its door for me. In a less than virtuous reaction I simply hailed another cab. But being a foreigner in Shanghai makes it tough to hide. When the driver whose car I broke appeared outside the open back door of the taxi where I thought I was out of view I fessed up.

“Duoshao qian?” I asked. (How much?)

“Wushi” (50) he replied.

Accepting the green 50 kuai bill (about $6 or $7 U.S. at that point) he then closed the door and went away. I didn’t admit guilt or shame or even try to bargain him down. I knew I was wrong. He didn’t press the matter. A person’s behavior is a matter of what another person will allow him or her to get away with.

I-thou (Wo-ni)

Relationships, not individual initiative, are declarative.

I raise the issue of morality, law, spirituality and politics since all four seem to meet now at the nexus that is Wenzhou. Legal and land use arguments of this case won’t define what eventually happens. But this new-fangled relationship to a God that has motivated millions, that’s a force to be negotiated.

We say who’ll you’ll be after you die!

I once did a story about a politburo member who declared that the Party would determine the reincarnated destiny of the next Dalai Lama. As in where his soul ends up. This is a political issue.

A little too Christian

The Washington Post’s Xu Yangjingjing explains officials near the Wenzhou church were “…concerned that Christianity was growing too fast and in an “unsustainable” manner…” which is a lot closer to the point than any specifics about how big the cross is on top of the building or according to whose timetable certain rules and regs were or were not met.

China Aid News, which defines itself as a human rights group that promotes religious freedom (two things the Party is no fan of) is distributing this story on its affiliated Christian News Network. In it they quote a Chinese lawyer as suggesting the worst is yet to come. “…the government has dispatched many people and organized them to get ready for the forced demolition. They even said they would use dynamite to blow the church up,” said Yang Xingquan, a lawyer keeping up with the case.

Branch Davidians & Wenzhou Christians

The fact that things could get to this point brings to mind the Branch Dividian showdown now some 20 years ago in which a 51-day siege by the ATF, FBI, and Texas National Guard ended in the death of the group’s leader, David Koresh, as well as 82 other Branch Davidian men, women, and children, and four ATF agents.

Recently, Malcom Gladwell reflects on same in The New Yorker. He describes a situation in which government agents, because of their own limitations, deduce that a religious group is a threat when, in fact, it is not.

The F.B.I. agent …didn’t grasp that he was dealing with a very different kind of group—the sort whose idea of a good evening’s fun was a six-hour Bible study wrestling with a tricky passage of Revelation….(a) more serious problem with the way the F.B.I. viewed the Branch Davidians was the fact that the agents could not accept that beliefs such as these—as eccentric as they were—were matters of principle for those within Mount Carmel. During the siege, two of the leaders of the F.B.I. team referred to Koresh’s theology as “Bible-babble” and called him a “self-centered liar,” “coward,” “phony messiah,” “child molester,” “con-man,” “cheap thug who interprets the Bible through the barrel of a gun,” “delusional,” “egotistical,” and “fanatic.” For another essay, published in “Armageddon in Waco,” the religious scholar Nancy Ammerman interviewed many of the F.B.I. hostage negotiators involved, and she says that nearly all of them dismissed the religious beliefs of the Davidians: “For these men, David Koresh was a sociopath, and his followers were hostages. Religion was a convenient cover for Koresh’s desire to control his followers and monopolize all the rewards for himself.”

In the government’s eyes, the Branch Davidians were a threat.

Audio of Gladwell talking about his piece here.

Dialing down the conflict will require a delicate touch especially now that the dust-up has attracted international attention. It will require understanding and communication skills that were absent in Waco twenty years ago. It will also require rationality and pragmatism, two traits not usually associated with religious zealots. Face will be an issue, as it always is in China.

The “Jews” of China

Wenzhou also have a unique role to play. Back in the Cultural Revolution, this city was where capitalism thrived, despite the hyper-politics of the day, as Scott Tong and I reported in 2007 over the airwaves of American Public Media’s business and economics show Marketplace (fast forward to 22:22 to cue the audio).

CAB DRIVER [translation]: Wenzhou people can endure suffering. A lot of suffering.

TONG: In the 1960s, this was one of China’s poorest places: mountains on three sides, water on the other. That forced the Wenzhou people to get creative. They started manufacturing simple items like shoes and trinkets: mass producing before anyone else here.

MARCUS: Birthplace of capitalism in China.

MARCUS: Let’s head to the open market.

MAN IN MARKET [translation]: We Wenzhou people always knew how to do business. Why? Because we had to. We had no land, no infrastructure.

TONG: In just one generation, Wenzhou turned itself into a global manufacturing powerhouse.

So, if there’s any place set for a showdown, this would be it. And if there’s any time for a showdown, there may be no arguing with the fierce urgency of now. Let us hope and pray extremism and passion don’t create an end like Masada, the fortification in the Judaen Desert overlooking the Dead Sea where in the year 73 C.E. a siege by imperial Roman troops ended with the mass suicide of 960 Jewish rebels and their families. The last rebel, as legend tells it, fell on his own sword. This would be a good time for China’s Communist Party to learn from history.

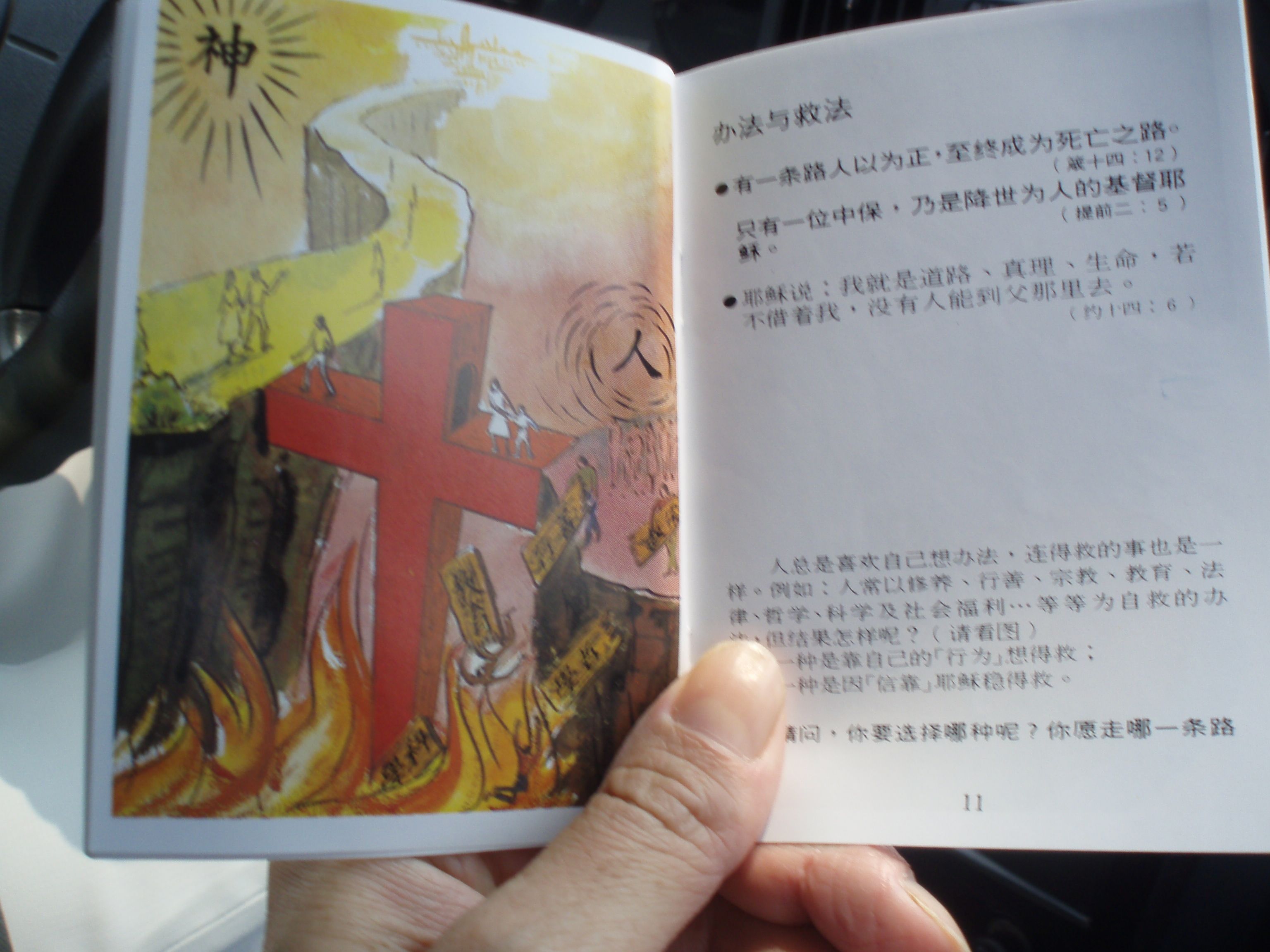

(Photo: A Beijing taxi driver during the Olympics showed me what he keeps above his viser.)

My friend, Jason Walker adds: 1) There are so many flavors of Christianity (Catholic, Protestant, high/low Church, social justice, spiritual practices, etc) that the Gov’t probably doesn’t understand or know how to engage. 2) if Christianity is going to significantly (change) Chinese culture via a sustained process, it will be a) via the underground Church, b) by helping Chinese culture through the growing pains of Modernism to Post-Modernism. 3) There are often a significant # of Christians (as may be said about other religions) who have not thoroughly studied the primary teachings of their own religion. A large portion of Chinese Christians are still trying to figure out what following Jesus means in a Sino-Confucian culture.