The Oriental Morning Post

Shanghai, China

A friend’s mother from Holland and a local woman in Laos embrace.

By Bill Marcus

The Vietnam-era White House never fully debated the policy credited with the Vietnam War, or the bombing of Vietnam’s neighbor Laos.

Between 1964 and 1973, American flyers dropped over four billion pounds of bombs on neutral Laos. The Laos should hate Americans like me, I thought, much like many parts of the world hate Germans. But the complete opposite turned out to be true. When I visited in January, I was welcomed with only smiles, and left alone to process a guilt stoked by anti-Iraq war Europeans during the first part of my vacation in Thailand.

On an early morning stroll through the Northern township of Nong Khiaw, I saw families drawing water form the river and wells, and cultivating early morning fires for cooking. It was easy to understand why the locals had taken refuge in the caves. The towering karst mountains, like parental wombs, would always shield them. Nature protects the innocent.

Guilt Comes Home

Off the main road, a woman was sweeping a field. As I approached she retreated to a table where a sign said admission was 50 cents. She handed me a key. A key? In the middle of nowhere? Because I have lived in Asia so long I simply accepted what was and walked along a dried rice patty knowing my question as to what it unlocked would be answered. From the mud and cement rose a steep flight of steps. In the cement was a date 11-9-2001. Coincidence?

I ascended to a reinforcing rod gate held in place by a bicycle lock. Inside the cave I found a sign: “Bedroom in War.” How fast, I wondered, does one need to climb to get out of the way of falling bombs?

Two mornings later, an hour by boat up the Nam Ou in Muang Ngoi, I listened as a 51 year-old man recalled his childhood in the caves. The bombs fell daily from 6am to 10pm. There was no school for seven years. His village of 80 survived on rice and dried buffalo meat from the Chinese. People courted and married in the caves, planned their lives there. Tired workers, the hard of hearing, or the elderly out beyond curfew, were killed. It ended when Nixon came to China, he said.

The After Effects of Battle

The shells now act as planters, ornaments, and buildings. Almost biblically, American instruments of war have been “beaten into ploughshares” by the Laos.

In Vientienne, at the National History Museum, pictures and slogans explained how the ordinances that fell every eight minutes continue to kill and impede progress: “Building Better Roads Can Have Explosive Results in Laos” and “A Killer Crop.” On one wall hung 41 simple black and white photos entitled “National Heroes.”

They were of housewives in tribal garb and handsome, passionate young men. I retrieved a guide from the front desk to praise the power of the pictures. These persons carried the fruit, rice, and water to their countrymen to keep them alive, he said.

When I was alone I cried as I had in the cave.

“Same in Vietnam, but more,” said a Frenchman. “Seventy-five years of war. It’s terrible. Don’t know why.”

My government kept the bombing a secret much today like they forbid the filming of caskets returning from Iraq.

Leaving the Past Behind

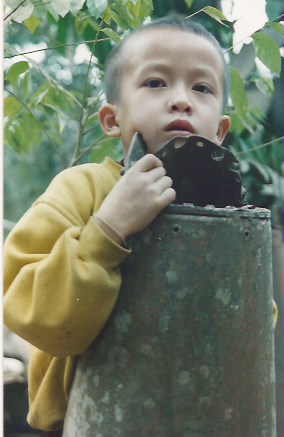

At the University, where I study and teach, I showed my Lao classmates portraits of the self-assured children posing on shells that still had the loading instructions and the place and date of manufacture on them. “Why hadn’t the people confronted me or hated?” I asked them.